There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed.

Through a unique style of unadorned prose and blatant disregard for adjectives, Ernest Hemingway’s work shaped the course of early 20th century American literature. He was the unapologetic antithesis of other celebrated writers of the time, and he bled for his work.

Hemingway lived through both world wars; serving as an ambulance driver in the First and as a war correspondent in the Second (as well as the Spanish Civil War). These rugged experiences arguably influenced his fearless and physical nature, as well as his literary works. From bullfighting in Spain to romantic afternoons in Paris, his life was filled with wanderlust, women, and writing.

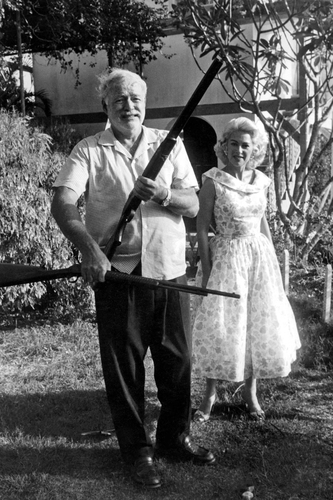

He strived to live as he meant to, always making a show of it along the way. On the surface, he was a man with a larger than life presence: a big drinker and womaniser. A man of heavy beard and brilliant mind. Yet, he hid some troubling vulnerabilities underneath all the bravado. He fought depression and anxiety in his later years; regularly consuming beer and gin for breakfast. It led to him losing the function to write. He lacked self-control and lost productivity — his defining traits. In 1961, Hemingway killed himself with his favorite double-barrelled shotgun.

His legacy resides in not just a body of work left behind, though, but in a contemporary writing style subsequent writers either copied, or avoided completely. It represented a shift from 19th century elaboration, to a more focused narrative told through dialogue and basic action — even silence. Fundamentally, he practiced economy in his writing: he got everything he could out of the fewest words. He was a generation defining writer — epitomised by his winning of the Pulitzer prize in 1952 for The Old Man and the Sea and the Nobel literature prize in 1954.

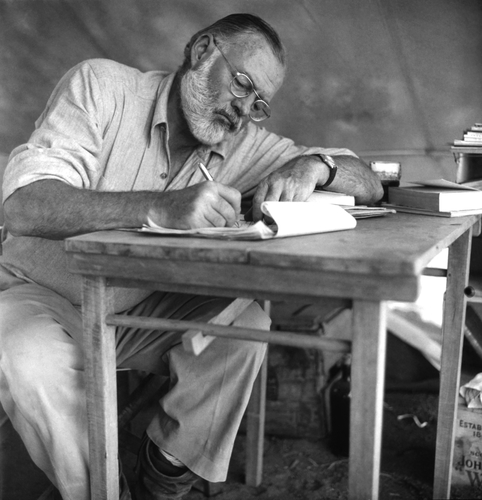

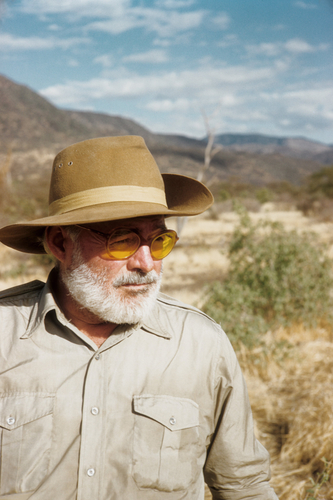

-

Hemingway, 1960

Photo by: Loomis Dean © Life Picture Collection

View -

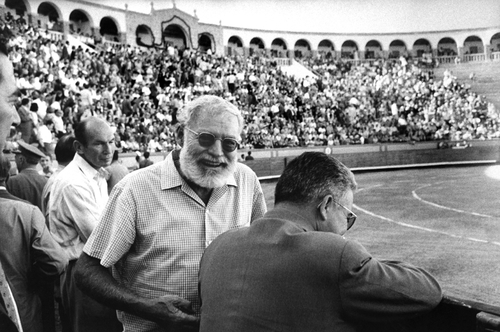

Hemingway in Madrid

Photo by: Zumapress / Bridgeman Images

View -

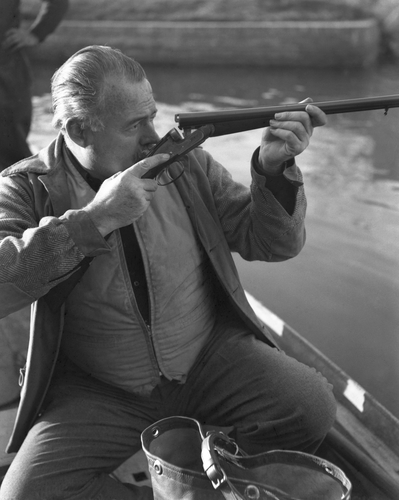

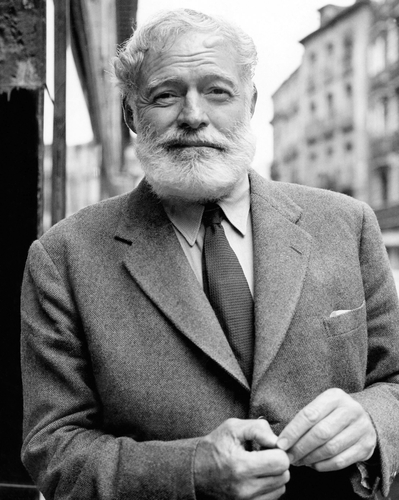

Hemingway in Venice

Photo by: © Archivio Arici / Bridgeman Images

View -

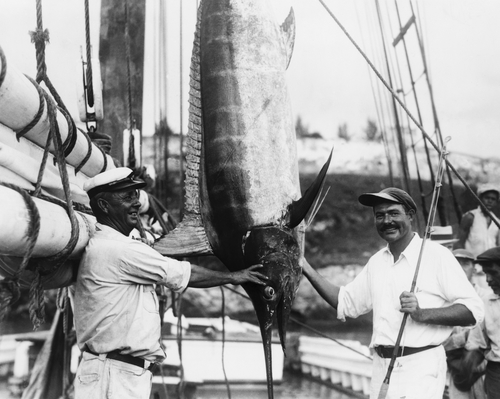

Ernest Hemingway with Marlin

Photo by: King Rose Archives

View -

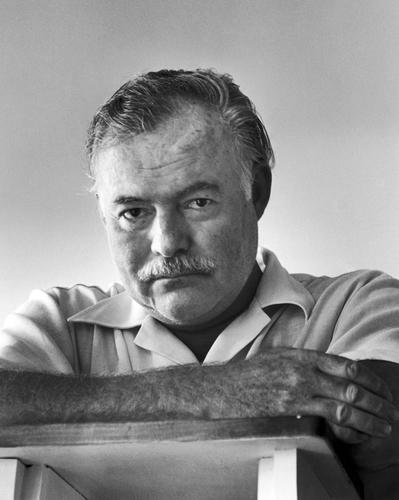

Ernest Hemingway, 1959

Photo by: King Rose Archives

View -

Hemingway at a Horse Race

Photo by: AGIP / Bridgeman Images

View -

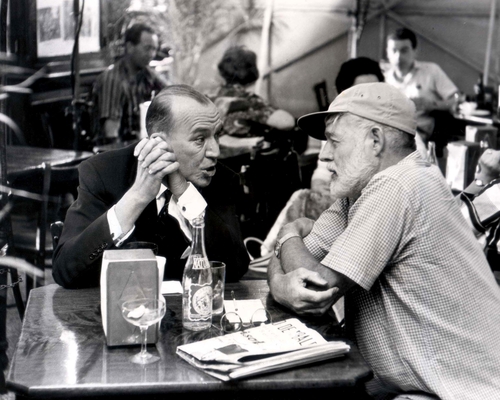

Hemingway and Carol

Photo by: Jerome Brierre / Bridgeman Images

View